Digital Speed Controller using RTAI/Linux

By Sreejith N

Speed control of an Industrial motor may sound complicated, but it's not as complex an affair as it sounds. What's interesting is that a PC powered with a Linux based RTOS can be used to control anything from a small motor to a complex industrial drive with the utmost reliability. This article presents the implementation of a Digital PI (Proportional+Integral) Controller on a PC running RTAI (Real Time Application Interface).

Control Systems

Control Systems can be broadly divided into two categories: open loop systems and closed loop systems. Systems which do not automatically correct the variations in their output are open loop systems. This means that the output is not fed back to the input for correction. For instance, consider a traffic control system where the traffic signals are operated on a time basis. The system will not measure the density of the traffic before giving the signals, thereby making it an open loop system.

Consider now a temperature control system, say an air conditioner. Output of this system is the desired room temperature. Obviously this depends on the time for which the supply to heater/cooler remains ON. Depending on the actual temperature sensed by sensors and the desired temperature, corrective measures are taken by the controller. Thus the system automatically corrects any changes in output by monitoring the input, hence making it a closed loop system.

An open loop system can be modified into a closed loop system by providing feedback. The provision for feedback automatically corrects the changes in the output due to disturbances. Hence, the closed loop system is also called an automatic control system. The general block diagram of an automatic control system is shown below.

![[csblockdiagram]](misc/sreejith/system.png)

Automatic controller

A controller is a device introduced into the system to sense the error signal and to produce the required control signal. An automatic controller compares the actual value of the plant output with the desired value, determines the deviation, and produces a control signal which will reduce the deviation to zero or to a smaller value. According to the manner in which the controller produces the control signal (called control action) controllers are classified as proportional(P), integral(I), derivative(D) and their combinations( PI, PD and PID).

The proportional controller is a device that produces a control signal u(t), which is proportional to the input error signal, e(t) (error signal, the difference between actual value and desired value), i.e.:

u(t) = Kp * e(t)where Kp = proportional gain or constant; a proportional controller amplifies the error signal by an amount Kp. The drawback of the P-controller is that it leads to a constant steady state error. Integral control is used to reduce the steady state error to zero. This device produces a control signal u(t) which is proportional to the integral of the input error signal:

u(t) = Ki * integral { e(t)*dt }

where Ki = integral gain or constant.

Integral control means considering the sum of all errors

over an interval, so this always gives us a measure of variation

over a constant interval. The other choice is derivative control where the

control signal (u(t)) is proportional to the derivative of the input error

signal (e(t)). We consider the derivative of e(t) at a given instant as

the difference between present and previous errors. A large positive

derivative value indicates a rapid change in output variable (here, the

speed of the motor). In other words, the rate of change of speed is greater.

The drawback of the integral controller is that it may lead to oscillatory

response. For these reasons combination of P, I and D are used. Most

(75-90%) of controllers in current use are PID. In this article,

we shall look at the design of a PI controller.

The PI controller looks at:

- The current value of the error,

- The integral of the error over a recent time interval.

This not only determines how much correction to apply, but for how long. Each of the above two quantities are multiplied by a `tuning constant'( Kp and Ki respectively) and added together. Depending on the application, one may want a faster convergence speed or a lower overshoot. By adjusting the weighting constants, Kp and Ki, the PI can be set to give the most desired performance. The implementation of software PI controller is discussed later in this article.

![[DigitalPIController]](misc/sreejith/digitalpi.png)

Today, digital controllers are being used in many large and small-scale control systems, replacing analog controllers. It is now common practice to implement PI controllers in its digital avatar, which means the controller algorithm is implemented in software rather than in hardware. The trend toward digital control is mainly due to the availability of low-cost digital computers. Moreover, as the complexity of a control system increases, demands for flexibility, adaptability and optimality increases. Digital computers used as compensators are a better option in such cases. A general purpose computer, if used, lends itself to time-shared use of other control functions in the plant.

Why real time

Using general purpose computers puts us at a disadvantage, if the operating system (OS) employs various tasks to be executed on a time shared basis. An example of such an OS is the standard version of GNU/Linux, where the time constraints required by the control system are not met.

The systems that ensure timing requirements are termed Real-Time (RT) systems. An appropriate OS should be used to satisfy time constraints.

Real-Time Systems

A real time system can be defined as a "system capable of guaranteeing timing requirements of the processes under its control". It must be fast and predictable. Fast means that it has a low latency, ie it responds to external, asynchronous events in a short time. The lower the latency, the better the system will respond to events which require immediate attention. Predictable means that it is able to determine a task's completion time with certainty. It is desirable that time-critical and non time-critical activities coexist in a real time system. Both are called tasks and a task with a hard timing requirement is called a real time task.

What is RTAI?

RTAI stands for Real Time Application Interface. Strictly speaking, it is not a real time operating system, such as VXworks or QNX. It is based on the Linux kernel, providing it with the ability to make itself fully pre-emptable. RTAI offers the services of the Linux kernel core, adding the features of an industrial real time operating system. It lets you write applications with strict timing constraints for your favourite operating system. Like Linux itself, this software is a community effort. You can follow this link to get more articles on experiments with RTAI.

PC parallel port as analog I/O interface

The PI Controller described in this article uses the PC parallel port as an analog I/O interface. Just two bits are used as analog interfaces through a technique called Pulse Width Modulation (PWM). This technique allows an analog interface to be built without the use of A/D or D/A converters, and analog voltages and currents can be used to control processes directly. As intuitive and simple as analog control may seem, it is not always economically attractive or practical. Analog circuits tend to drift over time and can, therefore, be very difficult to tune. By controlling analog circuits digitally, system costs and power consumption can be drastically reduced. Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) is a powerful technique for controlling analog circuits with digital signals. PWM is a way of digitally encoding analog signal levels. The duty cycle of a square wave is modulated to encode a specific analog signal level, as shown in this figure:

![[PWMwave]](misc/sreejith/pwm1.png)

The PWM signal is still digital because, at any instant, it is either on or off. The relation between the on time and the off time varies according to the analog level to be represented. Given a sufficient bandwidth, any analog value may be encoded with PWM.

![[PWMGenerationWaveForm]](misc/sreejith/pwm.png)

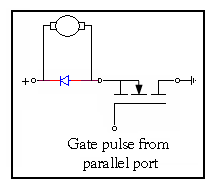

In this work, PWM technique is used to generate the gating signals for the chopper circuit. The speed of a DC motor can be controlled by varying its input voltage. A DC chopper circuit can do this job.

DC Chopper

A chopper is a static device that converts a fixed DC input voltage to a variable DC output voltage. A chopper may be thought of as a DC equivalent of an AC transformer since they behave in an identical manner. Chopper systems offer smooth control, high efficiency, and fast response.

Power semi-conductor devices used for a chopper circuit can be power BJT and/or power MOSFET. Like a transformer, a chopper can be used to step up or step down the fixed DC input voltage. Here, for motor speed control, a step-down chopper circuit with a power MOSFET is used. It is basically a high speed semiconductor switch. It connects source to load and disconnects the load from source at a high speed according to the gating signal. The average load voltage is given by

![[Chopperequation]](misc/sreejith/choppereqn.png)

where Vs is the source voltage, Ton is the on-time, Toff is the off-time, T (the sum of Ton and Toff) is the chopping period, and Ton/T is the duty cycle.

Preparing The Parallel Port

Although the parallel interface is simple, it can trigger interrupts. This capability is used by the printer to notify the lp driver that it is ready to accept the next character in the buffer. A simple outb() call to a control register makes the port ready to generate interrupts; the parallel interface generates an interrupt whenever the electrical signal at pin 10 (the so-called ACK bit) changes from low to high. The simplest way to force the interface to generate interrupts is to connect pins 9 and 10 of the parallel connector. A short length of wire inserted into the appropriate holes in the parallel port connector on the back of the system will create this connection. Pin 9 is the most significant bit of the parallel data byte.

Real time speed controller

The figure below represents the closed loop speed control of a 6V DC motor controlled by a chopper circuit. The duty cycle of the chopper is controlled using gating signals (PWM) from the PC parallel port. The PC is running the speed sensing (shaft encoder) module to read the current speed measured by the encoder. This device works by generating a square wave pulse produced when a perforated disc (keyed onto the shaft of the motor) cuts an IR beam. This square wave pulse train is fed back to the 10th pin of the parallel port. The controller program is running as a hard real time user program.

![[RealTimeSpeedController]](misc/sreejith/real_time_speed_controller.png)

The well-implemented PI controllers are usually hard real time systems. I have implemented a Digital PI Controller in a standard PC running Linux/RTAI (Linux-2.4.24 kernel patched with the RTAI-3.1). The I/O was done by PWM through two pins of the parallel port: one for input and the other for output, dispensing with the need for an A/D converter which is the most expensive component in a data-acquisition system. The PWM coding/decoding is handled by software routines implemented in Linux threads with LXRT RTAI hard real time constraints. The main routine, which is responsible for the actual PI calculation has also been implemented in a thread with hard real time constraints. The communication between threads was made through global variables. The controller program produces the necessary actuating signal (in terms of a PWM pulse), which in turn depends on an error signal produced by the difference of the set speed (a constant in the program) and the present speed. The chopper varies the average DC output voltage, used to control the speed of the DC motor. The motor used here is a small 6/12 V motor commonly found in most tape recorders. The following sections present the speed sensing (shaft encoder) module and the controller program followed by a brief description of the same.

Speed sensing (shaft encoder) module

Once interrupts are enabled, the parallel port generates an interrupt whenever there is low to high transition at pin 10 (ACK bit). This module includes the operations that should be performed when the interrupt occurs. The 'init_module' function registers a handler for interrupt number 7 (IRQ number). In the first execution of function 'lpt_irq_handler (void)' the count is zero; the control enters the if statementi, and the 64-bit time stamp counter (tsc) value is obtained by rdtsc macro function defined in 'msr.h'. By getting two tsc values at consecutive interrupts, the number of CPU clock cycles in between these interrupts can be calculated and hence the frequency. Frequency thus measured is communicated with a userspace program via a FIFO. Thus the userspace program can calculate the real-time speed. Here is the code which implements this idea:

#define MODULE

#include <linux/kernel.h>

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <rtai.h>

#include <rtai_sched.h>

#include <rtai_fifos.h>

#include <asm/io.h>

#define rdtsc(low,high) \ /*define rdtsc(low,high)*/

__asm__ __volatile__("rdtsc" : "=a" (low), "=d" (high))

#define TICK_PERIOD 1000000 /*1ms*/

#define TASK_PRIORITY 5

#define STACK_SIZE 4096

#define FIFO 0

#define LPT_IRQ 7

#define LPT_BASE 0x378

static unsigned int cpu_clock_count;

static RT_TASK rt_task;

static RTIME tick_period;

static void fun(int t) {

int count=0;

while(1) {

rtf_put(FIFO, &cpu_clock_count, sizeof(cpu_clock_count));

if(count==450) {

rtf_reset(FIFO);

count=0;

}

rt_task_wait_period();

}

}

static void lpt_irq_handler(void) {

static unsigned int low1,high1,low2,high2,count=0;

if(count==0)

rdtsc(low1,high1);

else {

rdtsc(low2,high2);

if(count==100)

count=1;

cpu_clock_count=low2-low1;

low1=low2;

high1=high2;

}

count ++;

rt_ack_irq(7);

}

int init_module(void) {

RTIME now;

int result;

outb(0x0,LPT_BASE);

result = rt_request_global_irq(LPT_IRQ, lpt_irq_handler);

if(result) {

rt_printk("rt_request_global_irq [7]......[failed]\n");

return result;

}

rt_enable_irq(LPT_IRQ);

outb(inb(0x37a)|0x10, 0x37a);

rt_printk("rt_request_global_irq [7]..... [ OK ]\n");

rt_set_periodic_mode();

rtf_create(FIFO, 4000);

rt_task_init(&rt_task, fun, 0, STACK_SIZE, TASK_PRIORITY, 0, 0);

tick_period = start_rt_timer(nano2count(TICK_PERIOD));

now = rt_get_time();

rt_task_make_periodic(&rt_task, now + tick_period, tick_period);

return 0;

}

void cleanup_module(void) {

outb(inb(0x37a)&~0x10, 0x37a);

rt_printk("rt_free_global_irq [7].... [ OK ]\n",

rt_free_global_irq(LPT_IRQ));

stop_rt_timer();

rt_printk("stop_rt_timer ..... [ OK ]\n");

rtf_destroy(FIFO);

rt_busy_sleep(10000000);

rt_task_delete(&rt_task);

}

The rt_request_global_irq and rt_enable_irq functions together instruct the RTAI kernel to service IRQ 7 (which is the parallel port interrupt). After compiling this module, insert it into the kernel address space using the "insmod" or the "modprobe" command, and check "/proc/modules" to ensure that it loaded successfully.

Controller program

The controller program is responsible for three things:

- Reading the current cpu_clock_count from the speed sensing module, ie from the FIFO, which is stored in an array for future reference;

- The PI task, and,

- Encoding the PI digital output, which is stored in a variable, into an external PWM wave signal which is the gating signal for chopper circuit.

The algorithm used for implementing the PI controller can be summarized as follows:

- Create a periodic task with period Tc

- Read the state of the parallel input pins

- Compute the control signal and update PWM signal

- Update the output-write thread

- Wait for the next task period Tc.

The main function creates five hard real-time threads which are shown in listings 1-4. An LXRT task starts out as an ordinary POSIX thread. It gets transformed to a hard, real-time thread by calling a function available as part of the LXRT library. The effect of this transition is that the thread is no longer managed by the normal Linux Scheduler - it comes under the supervision of the RTAI Scheduler, which guarantees that its timings do not get disturbed by activities taking place within the Linux kernel or in other user-space threads. The main() thread runs as a low priority task.

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <rtai.h>

#include <rtai_sched.h>

#include <rtai_fifos.h>

#include <asm/io.h>

#innclude <rtai_lxrt.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <math.h>

#define FIFO 0

#define BASE 0x378

#define CPU_CLOCK 1675888202.0 /* Enter your Cpu clock frequency*/

#define Kp 3

#define Ki 0.01

#define set_point_speed 0 /* Enter set point speed*/

#define TIMERTICKS 5000000 /*5ms*/

volatile int stop = 0;

static float cofk,Vm_sin=5,Vm_tri=10;/*Vm_=Vmax*//*n, no.of samples taken=400*/

sataic int eof[100],n=400,rt_speed;

static RTIME tick_period,now;

unsigned int cpu_clock_count;

static float Vsin_k [100], Vtri_k [100];

static float Mag_level_Var_sin=64.0,

Mag_level_Var_tri=256.0;/*Magnitude levels*/

int main ()

{

RT_TASK *task;

pthread_t th0,th1,th2,th3,th4;

task = rt_task_init(nam2num("main"), 10, 4096, 0);

if(task == 0) exit(1);

rt_set_periodic_mode();

tick_period = start_rt_timer(nano2count(TIMERTICKS));

now = rt_get_time();

pthread_create(&th0, 0, rt_task_pid, 0);

pthread_create(&th1, 0, rt_task_in_put, 0);

pthread_create(&th2, 0, rt_task_out_put, 0);

pthread_create(&th3, 0, rt_task_sin, 0);

pthread_create(&th4, 0, rt_task_tri, 0);

getchar();

stop = 1;

pthread_join(th0, 0);

pthread_join(th1, 0);

pthread_join(th2, 0);

pthread_join(th3, 0);

pthread_join(th4, 0);

stop_rt_timer();

rt_busy_sleep(10000000);

rt_task_delete(task);

return 0;

}

Follow this link to download the code.

The PI task

The PI task is the core of the application, where the controller calculation is actually made. The PI controller receives as input the error, given by e(t) = r(t) - y(t) and computes the control variable c(t) which is its output. The control signal c(t) is calculated from the discrete PI equation given below:

![[piequation]](misc/sreejith/pieqn.png)

- The current value of the error;

- The integral of the error over a recent time interval;

- Compute control signal and update PWM signal;

- Update output-write thread

This thread has been assigned the fifth highest priority among the five hard real time tasks.

The code is given in Listing 1.

void* rt_task_pid(void *arg) {

RT_TASK *task;

static int n=0,k=0,sum=0;

task = rt_task_init(nam2num("rtl0"), 4, 4096, 0);

rt_task_make_periodic(task, now + tick_period, tick_period);

rt_make_hard_real_time();

while(!stop) {

eof[k]=set_point_speed - rt_speed;

while(n<=k) {

sum=sum + eof[n];

n++;

}

cofk=Kp*(eof[k]+(Ki/Kp)*sum);

if(cofk>0) Vm_sin=Vm_sin+0.5;

else if(cofk<0) Vm_sin=Vm_sin-0.5;

n=0;

k++; sum=0;

if (k==99) k=0;

rt_task_wait_period(); /*5ms*/

}

rt_make_soft_real_time();

rt_task_delete(task);

}

Task `rt_task_out_put'

Listing 2 shows a hard Real-time LXRT program generating a PWM running at a frequency of 50Hz on a parallel port pin to feed the motor drive (DC chopper). The PWM is generated by comparing the instantaneous values of a sine wave and a triangular wave of required frequency. The instantaneous values of the sine wave and the triangular wave are generated in the threads given in Listing 3. These instantaneous values are compared in the thread rt_task_out_put to generate the PWM. This thread has been assigned the third highest priority.

void* rt_task_out_put(void *arg) {

RT_TASK *task;

static int i;

task = rt_task_init(nam2num("rtl1"), 2, 4096, 0);

iopl(3);

rt_make_hard_real_time();

while(!stop) {

if(Vtri_k [i]>=Vsin_k [i]) {

outb(0x1,0x378);

rt_sleep(nano2count(50000)); /*50us*/

}

else if(Vtri_k [i]<Vsin_k [i]) {

outb(0x0,0x378);

rt_sleep(nano2count(50000)); /*50us*/

}

i++;

if(i==99) i=0;

}

rt_make_soft_real_time();

rt_task_delete(task);

}

Listing 3, below, shows the code for generation of sinusoidal and triangular function values used in the output thread for generating the PWM gating signals.

/*To Generate Sine Wave*/

void *rt_task_sin (void *arg) {

RT_TASK *task;

static float f = 50, td, t, Vsin_t, s; /*frequency =50Hz*/ /*s =

Step size*/ /* td = Time delay between two samples*/

static float Auto_correction;

static int i,j;

task = rt_task_init(nam2num("rtl1"), 1, 4096, 0);

s = 2*Vm_sin/Mag_level_Var_sin;

td = 1/(f*n);

Auto_correction = (Mag_level_Var_tri - Mag_level_Var_sin)/2;

rt_make_hard_real_time();

while (!stop) {

t = i*td;

Vsin_t = Vm_sin*sin(2*M_PI*f*t);

Vsin_k [j] = (Vsin_t+Vm_sin)/s + Auto_correction;

rt_sleep(nano2count(50000)); /*50us*/

i++; j++

if(i == (n-1)) i=0; if(j==99) j=0;

}

rt_make_soft_real_time();

rt_task_delete(task);

}

/*To Generate Triangular Wave*/

void *rt_task_tri (void *arg)

{

RT_TASK *task;

static float f=100, td, Vtri_t, s, t;/*frequency =100Hz*/ /*s = Step

size*/ /* td = Time delay between two samples*/

static float SLOPE;

static int i,j;

task = rt_task_init(nam2num("rtl2"), 0, 4096, 0);

SLOPE = 4*Vm_tri*f;

td=1/(f*n);

s=2*Vm_tri/Mag_Control_Var_tri;

rt_make_hard_real_time();

while (!stop) {

t=i*td;

if (Vtri_k [j] = Mag_Control_Var_tri) {

Vtri_t = 1 * SLOPE * t;

Vtri_k [j] = (Vtri_t+Vm_tri)/s - Mag_Control_Var_tri/2;

rt_sleep(nano2count(25000)); /*25us*/

i++;

}

else {

Vtri_k [j]= 0.0;

i=1;

}

j++;

if(j==99) j=0;

}

rt_make_soft_real_time();

rt_task_delete (task);

}

Task `rt_task_in_put'

This task continuously reads values from the FIFO (note that the shaft encoder writes real-time speed to the FIFO) and stores it in the `cpu_clock_count' variable. The value of cpu_clock_count is converted to speed in RPM and is stored in `rt_speed'. This thread has been assigned the second highest priority. The code for this process is shown in Listing 4:

/*The Feed back Task*/

void* rt_task_in_put (void *arg)

{

RT_TASK *task;

task = rt_task_init(nam2num("rtl3"), 3, 4096, 0);

iopl(3);

rt_task_make_periodic(task, now + tick_period, tick_period);

rt_make_hard_real_time();

while(!stop) {

rt_speed=CPU_CLOCK*60/(float)cpu_clock_count;

rtf_get(FIFO, &cpu_clock_count, sizeof(cpu_clock_count));

rt_task_wait_period(); /*Tc =5ms*/

}

rt_make_soft_real_time();

rt_task_delete(task);

}

The real-time speed of the motor can be displayed either by running the code below as a thread, or by running main() as a GUI application by using FLTK/GTK.

/*Print Real Time Speed*/

void* task_show_report(void *arg)

{

while(!stop) {

printf("%d\n",rt_speed);

}

}

The complete controller code can be seen

here.

Conclusion

The above experiment illustrates the use of a PI controller for closed loop speed control of a small DC motor. The performance of this PI controller was found to be acceptable for such a motor. However, in attempting to model a converter along similar lines for a real large-scale industrial drive, I found that the large number of control parameters required a more in-depth and detailed controller design using the concepts of Control System theory.

I am a Linux enthusiast living in India. I enjoy the freedom and power that

Linux offers. I must thank my mentor Mr. Pramode C. E. for introducing me to

the wonderful world of Linux.

I completed my B-Tech in Electrical and Electronics Engineering from Govt.

Engineering College, Thrissur (Kerala, India) (2001 - 2005). Presently I am

in search of a Linux-based job.

I spend my free time reading books on Linux and exploring the same. I have

an avid interest in Linux Kernel Programming and have done some projects to

that effect. My other areas of interest include device drivers, embedded

systems, robotics and process control.

![[BIO]](../gx/authors/sreejith.jpg)